Self-Made Man: A Review

If you're interested in lesbian takes on men!

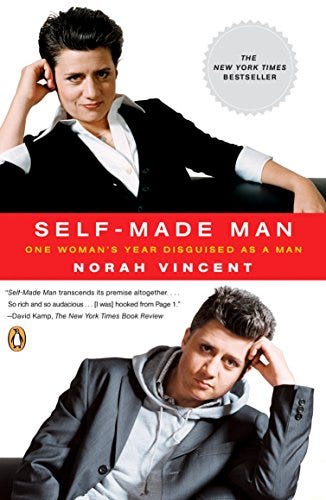

At the beginning of this month, I wrote about Norah Vincent, author of the book Self-Made Man: One Woman’s Journey Into Manhood and Back Again. The book describes Vincent’s year-and-a-half adventure of living as a man named Ned, and reading it was long overdue for me. Well, I’ve now read it and had some time to reflect, and I’m very happy that I had the opportunity to do so.

I’d say the book was largely what I expected—as I wrote in my previous piece, I’ve never taken the oppressor/oppressed view to sex relations, so I didn’t really have any terrible notions of men to shatter.

However, in a way, I almost expected it to be more sympathetic to men. While I was researching Vincent for my previous article, I came across many comments and reviews from men online who were very happy and grateful that such a book had been written. The way some of these men talked, you’d think the whole thesis of the book was that men have it much, much worse than women, and they were happy a woman was finally realizing that.

However, I found the book to be very even-handed, with plenty of focus on the difficulty of navigating the world as a woman, and on the fact that it is men who often make this difficult.

In fact, the book begins with some passages describing how different it is to walk down the same street when perceived as a woman or man.

As a woman, you couldn’t walk down those streets invisibly. You were an object of desire or at least semiprurient interest to the men who waited there, even if you weren’t pretty—that, or you were just another pussy to be put in its place. Either way, their eyes followed you all the way up and down the street, never wavering, asserting their dominance as a matter of course. If you were female and you lived there, you got used to being stared down because it happened every day and there wasn’t anything you could do about it.

But that night in drag, we walked by those same stoops and doorways and bodegas. We walked by those same groups of men. Only this time they didn’t stare. On the contrary, when they met my eyes they looked away immediately and concertedly and never looked back. It was astounding, the difference, the respect they showed me by not looking at me, by purposely not staring.

Vincent also described the sometimes paralyzing fear she felt in all-male spaces, like the first time she walked into the bowling alley for her bowling league and especially when she was getting ready for an all-male wilderness retreat:

I was going into the woods alone with a bunch of guys who thought I was a man and had serious rage issues about women. They’d even talked about tearing women to pieces or chopping them up with axes.

The strip club chapter likewise provided insight into how at least some men think about, speak about, and view women:

I couldn't help putting myself in the stripper's place, imagining all those dehumanizing pairs of eyes coursing over me, and the emcee’s voice tangling me in front of them as bait. I couldn't separate the stripper’s act from the hopeless life that I thought had probably let her or trapped her into doing this for a living.

Similarly, during her stint as a salesman, Vincent was taken aback by the many highly crude and sexualized remarks that her male coworkers would make about women in the office and women in general.

I think the fact that many men liked what Vincent did despite the fact that she didn’t hide or downplay the darker side of being male showcases that they were grateful to simply be considered equally human. I wouldn’t say that her final thesis was that men have it worse but that they have different problems and that they certainly don’t have it, in any objective sense, “better.”

I felt that the dating chapter really captured a lot of sympathy and understanding for both sexes, though Vincent’s thoughts on the male position really stood out since it is not the side that usually gets the sympathy.

Dating was not a fun experience for her. In fact, Vincent described it as the hardest thing she had to do as Ned. As a man, she was expected to make the first move, but she also had to bear the brunt of crushing rejection. Women also seemed to have quite polar expectations of men—to be emotionally available and sensitive but also manly and stoic.

Personally, while reading the chapter, I found myself very irritated at the, dare I say, entitled attitude a lot of the women had on the dates. They expected to be impressed but were often terrible company themselves. As Vincent writes:

“Pass my test and we’ll see if you’re worthy of me” was the implicit message coming across the table at me. And this from women who had demonstrably little to offer. “Be lighthearted,” they said, though buoyant as lead zeppelins themselves. “Be kind,” they insisted in the harshest tones. “Don’t be like the others,” they implied, while having virtually condemned me as such beforehand.

Vincent even described herself as having turned into a “momentary misogynist,” though she recognized her dislike of women as irrational. Eventually, she came to an understanding of the frustrating predicament of both sexes when it comes to heterosexual dating and love, and even commented on how she came to find deep love and genuine attraction for “real men” in female heterosexuality—not for women in men’s bodies.

That brings us to another thread that caught my interest throughout the book: even though Vincent may have been butch for a woman, she came off as so feminine as a man that many people she interacted with thought she was gay.

Vincent considered herself quite stereotypically masculine from an early age, writing:

Practically from birth, I was the kind of hard-core tomboy that makes you think there must be a gay gene.

Same, Norah, same.

Later, she goes on to explain:

I’d been considered a masculine woman all my life. That’s part of what made this project possible. But I figured that when I went out as a guy some imbalance would correct itself and I’d just be a regular Joe, well within the acceptable gender spectrum. But suddenly, as a man, people were seeing femininity busting out all over the place.

Every time Vincent made this observation, I couldn't help but think of TikToker Dylan Mulvany. I'm sure many people would describe Mulvany as quite effeminate. However, when he's all done up with his makeup and women's clothing trying to convince us that he is a “girl,” I can't for the life of me see anything feminine about him. To me, he comes off as a hyper little boy, and everything about his body screams “male” so much louder than if he was not trying to “present” as a woman.

Masculine women are 100% more of a woman than any man will ever be, and vice-versa, and this is something that Vincent learned the hard way.

When she was finished with her project, she checked herself into a psychiatric unit. The weight of the deception that she had to pull off as Ned, coupled with the difficulties of maintaining a separate identity, got to be too much to handle. She wrote:

First of all, Ned was an impostor and impostors who aren't sociopaths eventually implode. Assuming another identity is no simple affair, even when it doesn't involve a sex change. It takes constant effort, vigilance and energy. A lot of energy. It's exhausting at the best of times. You are always afraid that someone knows you are not who you say you are, or will know immediately if you make even the slightest false step. You are outside of yourself in two senses. First because you are always watching yourself from beside or above, trying to get the performance right and see the pitfalls coming, but also because you are always trying to inhabit the persona of someone who doesn't exist, even on paper. You don't have the benefit of a script or character treatment that can tell you how this person thinks, or what his childhood was like, or what he likes to do. He has no history and no substance, and being him is like being an adult thrown back into the worst of someone else’s awkward adolescence.

What a poignant observation that is easily applied to the mostly young people who have hopped on the gender identity bandwagon and are trying to present themselves as something that they are not, right down to the DNA in their cells.

Vincent made this point as well:

I believe we are different in agenda, in expression, in outlook, in nature, so much that I can’t help almost believing, after having been Ned, that we live in parallel worlds, that there is at bottom really no such thing as that mystical unifying creature we call a human being. Only male human beings and female human beings, as separate as sects.

Her experience of the stark and persistent differences between men and women is partly why I don't put a whole lot of stock in “socialization” vs. biology and genetics when it comes to human behavior. In my previous piece about Vincent, I ventured the thought that this is one topic I might disagree with her on.

However, after reading the book, I must confess I have a greater appreciation of the power of socialization on our behavior. I still contend that the way we socialize males and females will have its roots in biology, but I can see how it might differ wildly among cultures.

Many of the ways Vincent had always felt comfortable expressing herself as a woman really took people aback when she did so as a man, and it seemed obvious to her that, if she grew up as a man, she would have been socialized to know that. Now, perhaps as a real man, she would have felt naturally less inclined to act in certain ways but, of course, men are full human beings with a range of emotions and expressions of those emotions, and I do understand how that range would be narrowed by societal expectations. As Vincent remarked, she hardly ever interacted with anyone who didn’t treat her in a gender-coded way depending on if she was Ned or Norah.

All of this, she concluded, contributed to the fact that many men were suffering and isolated partly because they could not express and often even identify their emotions.

In the chapter describing her experiences at a men’s self-help group, Vincent writes:

To me this was amazing, the idea that a person could be incapable of expressing his emotions. Identifying and expressing my emotions had usually come fairly easy to me it had never occurred to me that some people not only didn't do this but didn't have the slightest notion how to do this. This, I now realize, is a highly privileged, largely feminine point of view, and one whose value and comparative rarity Ned has since made me appreciate.

“It was hard being a guy,” Vincent concluded. “Really hard.”

But what can be done about this? Well, she had a few thoughts on that as well, but they were a little bleak:

Men’s liberation isn’t a platform you can run on, even if it is the last frontier of new age rehabilitation: the oppressor as oppressed. In our age we feel no political sympathy for “man,” because he has been the conqueror, the rapist, the warmonger, the plutocrat, the collective nightmare sitting on our chests. Right? Right. “Boo hoo,” we say in the face of his complaint. “The tyrant weeps.”

Self-Made Man was published in 2006, and it’s hard for me to say that a lot has changed. While there were some anachronisms that were funny to read, like Vincent communicating with her dates over e-mail rather than social media DMs or dating apps, not much else about the book felt out of place, especially not when it comes to male-female relations. Our funny ideas about sex and gender don’t seem to have liberated men or women—in fact, it seems that we are more trapped than ever. This is why I think Vincent’s book should still be read by anyone looking for a greater understanding of humanity’s great divide.

Or help support my work with a one-time donation through PayPal!

People ask "nature or nuture?" but the correct answer is "yes."

So great...thanks for the excerpts and your thoughts about the book.